Source: Vasco da Gama, Portugal’s Columbus, Is Just as Controversial | HowStuffWorks

Key Takeaways

- Vasco da Gama, Portugal’s Columbus, was a controversial explorer known for using violence to secure trade routes in India and Africa.

- Da Gama’s expeditions were marked by aggressive tactics, including attacking unarmed civilians and setting a pilgrim ship on fire.

- Despite his controversial methods, da Gama played a key role in establishing European sea routes to India and is celebrated as a national hero in Portugal.

When school children learn about the Age of Discovery — the 15th- and 16th-century maritime exploits of Spain and Portugal, chiefly — they memorize a list of a half-dozen European men in funny hats who sailed bravely into uncharted waters to discover far-off lands. Among them is Vasco da Gama, a Portuguese explorer who was the first European to sail to spice-rich India by rounding the southern tip of Africa.

But just like his contemporary, Christopher Columbus, da Gama is a complex and controversial historical figure. A devout Christian and a loyal Portuguese subject, da Gama had no qualms about using violence — including against unarmed civilians — to force his way into the lucrative Indian and African trade routes dominated at the time by Muslims.

“Da Gama deserves to be recognized as one of the more heavy-handed explorers,” says Marc Nucup, a public historian at The Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. “He was willing to take what he wanted and get his way at the point of a canon.”

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, a history professor at UCLA who wrote an eye-opening book about da Gama, says that the Portuguese explorer left almost no personal writing or journals compared to the prolific Columbus, but that scraps of letters and journal entries penned by da Gama’s crew paint a “troubling” picture of an ill-tempered, even dangerous character.

“The accounts written by people on da Gama’s voyages portray someone who was, even by the standards of the time, a violent personality,” says Subrahmanyam.

Keeping Up with Columbus

In the 15th century, the Spanish and Portuguese were in a bitter race to find a sea route to India that bypassed the tortuously long and expensive overland trade route through unfriendly Ottoman and Egyptian territory. In 1488, the Portuguese took the lead when Bartolomeu Dias successfully navigated around the Cape of Good Hope (Dias called it the “Cape of Storms”) in modern-day South Africa and became the first European to reach the Indian Ocean.

But Dias returned with bad news for King João II of Portugal. The winds and currents in the Indian Ocean blew northeast to southwest, making it all but impossible to cross the sea from Africa to India. Nucup says that Dias didn’t understand how the seasonal monsoons of the region worked, and that the winds actually switched directions for half the year. Thinking it was hopeless, Portugal didn’t attempt another southern run to India for 10 years.

In the meantime, Columbus — who learned his trade in Portugal — discovered what he believed to be a western route to the Indies (or possibly Japan) for Spain in 1492. For the Portuguese, the pressure was high to stake their own claim to Oriental trade, so Manuel I, now king of Portugal, ordered a new expedition to India via the South African route, and in command of this mission wasn’t Dias, but Vasco da Gama.

Who Was da Gama?

Historians know little of da Gama’s early life, just that he was born sometime in the 1460s in the small coastal Portuguese city of Sines to well-positioned parents, a knight and a noblewoman, which afforded him a good education in navigation and advanced mathematics. At some point he gained practical experience on ships and may have become a captain as early as 20 years old.

Why did King Manuel I choose da Gama, then in his thirties, for the voyage to India? Nucup says that da Gama had proved a loyal enforcer when he was sent to put an end to a conflict between Portuguese and French merchants.

“Apparently he did a really good job seizing French vessels, so he gained the king’s trust,” says Nucup. “This is a guy who can get stuff done for me.”

First Voyage — Success Turns to Frustration

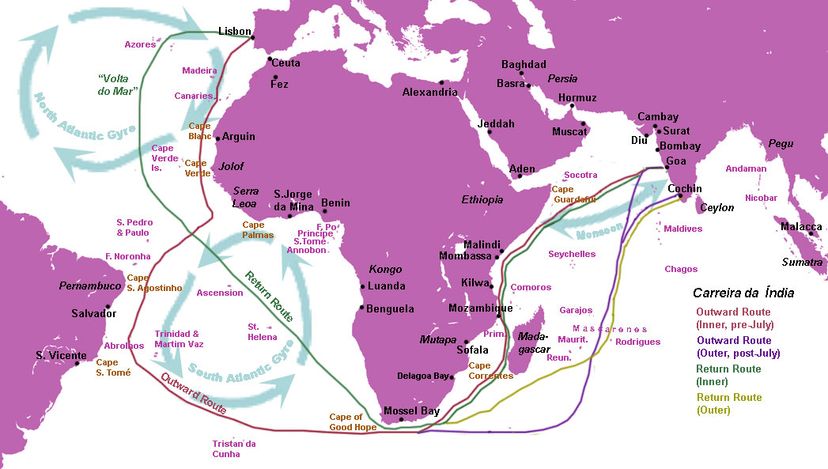

On July 8, 1497, da Gama set sail from Lisbon with four ships and 170 men, including his brother Paolo. There was nothing easy about navigating 15th-century sailboats through unruly seas, but da Gama wisely took Dias’s advice and swung far west into the southern Atlantic (just 600 miles, or 965 kilometers, from Brazil) to catch strong winds that would propel them eastward toward the tip of Africa.

The risky plan worked, and after 13 long weeks on the open water out of sight of land, da Gama landed in St. Helena Bay, just 125 miles (200 kilometers) north of the Cape of Good Hope on November 7, nearly four months after leaving Portugal. The expedition slowly worked its way around the stormy Cape and entered the Indian Ocean around Christmastime. But now came the real test, figuring out how to cross the sea to India. For that, he needed a knowledgeable local captain, who he hoped to recruit or kidnap from Eastern Africa.

Da Gama’s first major encounter with an African kingdom was in Mozambique, where he was poorly received, an experience that would be repeated throughout the first voyage. Nucup says that da Gama was following the example of Columbus, who had won over native leaders with simple European goods like bells, flannel and metalwork.

“But when da Gama stopped at ports in Eastern Africa and offered these items for trade, people would laugh at him,” says Nucup. “These weren’t impressive to local traders.”

In Mozambique, the Sultan and his people were actually offended and started to riot, says Nucup. Da Gama fled back to his ship and lobbed a few canon balls at the city as parting shots. The Portuguese were better received in the African kingdom of Malindi, where da Gama was able to recruit a local pilot who could guide them across the tricky Indian Ocean to their final destination.

After a 27-day journey, da Gama and his men arrived in Calicut, a coastal city in Southern India known today as Kozhikode. Subrahmanyam says that the Portuguese were “shocked” to find that Muslims were running the spice trade in India.

“They were under the impression that there were a lot of Christians in India and that these people would be their natural allies,” says Subrahmanyam.

Instead, da Gama found outposts of an extensive African-Indian trade network operated largely by Arab Muslims. Again, nobody in Calicut was impressed with the paltry goods the Portuguese had brought to trade for high-end spices. The local traders and merchants made it clear that gold was the only currency that mattered.

After a tortuous journey home against the monsoon winds, Da Gama returned to Lisbon nearly empty-handed, but he was still greeted as a hero for reaching his destination and making it home after two years and 24,000 miles (38,600 kilometers) at sea. Sadly, scurvy had claimed all but 54 of his 170-man crew including da Gama’s brother Paolo.

The Second Voyage — Things Get Ugly

Before da Gama returned to India, another Portuguese explorer named Pedro Álvarez Cabral was given command of an Indian expedition. Cabral sailed with a much larger crew of 1,200 men and 13 vessels, including one captained by Dias. Following da Gama’s route, Cabral swung far west to catch those helpful Antarctic winds, but he ended up swinging even farther west than intended and accidentally discovered Brazil, which he claimed for the Portuguese.

Cabral eventually continued on to India, encountering terrible storms that claimed four of his ships, including the one captained by Dias. When he finally arrived in Calicut, he met fierce resistance from the Arab Muslim traders, who killed some Portuguese sailors in an attack. Cabral responded by bombarding the city, raiding 10 Arab ships and killing an estimated 600 Muslims. It was a “diplomatic” style that da Gama would follow to terrible effect.

In 1502, da Gama set sail again for India in command of 10 ships and with his sights set on breaking the Muslim monopoly on the spice trade once and for all. On his way, he threatened African leaders with his canons in exchange for vows of loyalty to Portugal, but nothing compares to the campaign of terror he waged along India’s Malabar Coast.

In the most horrific incident, da Gama intercepted a ship carrying Muslim families returning from a religious pilgrimage to Mecca in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Da Gama locked up the passengers in the ship’s hull, and despite pleas from his own crew members not to do it, he set the pilgrim ship ablaze, slowly killing hundreds of men, women and children.

“Maybe he was trying to create an image for the Portuguese — you don’t mess with us,” says Subrahmanyam. “And that message did come across. The pilgrim ship incident cemented the reputation of the Portuguese as very dangerous and violent people in the Indian Ocean.”

In Calicut, there were more skirmishes between da Gama and Arab traders. Da Gama responded by capturing 30 unarmed local fishermen, dismembering their bodies and letting the remains wash in on the tide as a message of Portuguese power.

The combined cruelties of Cabral and de Gama succeeded in establishing Portuguese trading outposts in Calicut and in the southern Indian state of Goa, where Subrahmanyam says the Portuguese maintained an official presence until the 1960s.

Da Gama had married after his first voyage and went on to sire six sons and one daughter. He spent 20 years as an adviser on Indian affairs to the Portuguese king. In 1524 he was sent back to Goa as viceroy to deal with some corruption in the government the Portuguese established there. He soon got ill and died that same year in India.

Da Gama’s Legacy

Given da Gama’s questionable methods and the important contributions of Dias and Cabral, it’s fair to ask why da Gama is so famous and why school kids continue to memorize his name. Nucup says that you simply can’t tell the story of European exploration and colonization without da Gama.

“Was he a great explorer? No,” says Nucup. “But through his efforts, Portugal established a European sea route to India and eventually further to China and the Indies and helped create what would become the Portuguese overseas empire. Again, whether that’s progress or not is up for debate.”

Subrahmanyam says that one of the main reasons why da Gama’s name rings down through the centuries is because the Portuguese needed a national hero to rival Columbus.

“The Spaniards made a big deal of Columbus and the Portuguese were very annoyed with that,” says Subrahmanyam. “The Portuguese made a very deliberate attempt in the 16th century to build up da Gama as their Columbus.”

The best example of this Portuguese propaganda campaign was a 12-part epic poem called “The Lusiad, or The Discovery of India,” written by Portugal’s most famous poet, Luís de Camões. The poem, which portrays da Gama as a Greek-style hero rivaling not only Columbus, but Achilles and Odysseus, sealed the controversial explorer as a larger-than-life Portuguese hero.

HowStuffWorks earns a small affiliate commission when you purchase through links on our site.