Source: Venus facts — A guide to the 2nd planet from the sun | Space

Venus is the hottest and brightest planet in the solar system.

Venus’ atmosphere traps heat from the sun as an extreme version of the greenhouse effect that warms Earth. The temperature on Venus are hot enough to melt lead. (Image credit: ARTUR PLAWGO / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY via Getty Images)

Venus, the second planet from the sun, is the hottest and brightest planet in the solar system.

The scorching terrestrial (rocky) type planet is named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty and is the only solar system planet named after a female when following the International Astronomical Union designation of names that the astronomy community uses as a convention. (Other cultures have different names for celestial locations.)

Venus may have been named after the most beautiful deity of the Roman (and Greek) pantheons because it shone the brightest among the five planets known to ancient astronomers. In ancient Greek city-states, however, Venus was called Aphrodite.

Length of day: 243 Earth days

Length of year: 225 Earth days

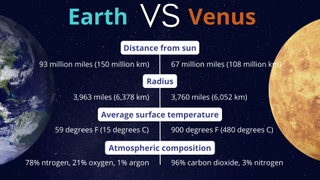

Distance from sun: 67 million miles (108 million kilometers)

Number of moons: 0

Surface temperature: 900° F (480° C)

Diameter: 7,520 miles (12,100 km)

Atmospheric composition: 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen.

In ancient times, planet Venus was often thought to be two different stars, the evening star and the morning star — that is, the ones that first appeared at sunset and sunrise. In Christian Latin, they were respectively known as Vesper and Lucifer. (In Christian times, Lucifer, or “light-bringer,” became known as the name of Satan before his fall.)

However, further observations of Venus in the space age show a very hellish environment. This makes Venus a very difficult planet to observe from up close because spacecraft do not survive long on its surface.

Related: What is a ‘morning star,’ and what is an ‘evening star’?

Planet Venus FAQs

How hot is planet Venus?

Temperatures on Venus reach 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius), which is more than hot enough to melt lead.

What is planet Venus made of?

Venus is made up of a central iron core and a rocky mantle, similar in composition to Earth. But Venus’ hellish atmosphere is made up of mainly carbon dioxide (96%) and nitrogen (3.5%) with trace amounts of carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, water vapour, argon, and helium making up the other 0.5%.

Planet Venus color

Venus is highly visible from Earth due to its reflective clouds. In the sky, Venus appears as a brilliant white object that is one of the brightest natural things in the night sky. Its maximum magnitude, or apparent brightness, is close to -5, according to NASA. (By comparison, the moon is roughly -14, The lower an object’s magnitude, the brighter it appears to the eye.)

Up close, NASA says the color of Venus is “rusty”, but not the kind of deep red rust one would find on the planet Mars. Rather, pictures NASA and others have sent back from Venus suggest a world with tinges of red, brown and yellow. Cornell University suggests that color comes from the number of volcanic rocks dotting the surface, as Venus is a highly active world.

The “real” color of Venus, however, is impossible to see from orbit due to the sulfuric acid clouds surrounding the planet. Pictures of Venus are thus only visible if an orbiting satellite has the ability to peer through the thick clouds. For a human explorer to see the surface, they would need to descend and to survive the oven-like temperatures and high pressures present down there. That harsh environment likely means that for now, we’ll be using robotic explorers to look at Venus for us.

The orbit of Venus lies along the ecliptic, which is the same pathway that the other planets, the sun and the moon also take in our solar system. That’s no coincidence, as the ecliptic represents the “plane” or the orientation of our solar system, which all goes back to how our solar system came to be. In practice, Venus being so close to other worlds means that conjunctions, or close encounters between celestial worlds, are quite common in Earth’s sky. Several times a year you will see Venus lining up with the moon, and more rarely, with other planets.

Size and temperature

Venus and Earth are often called twins because they are similar in size, mass, density, composition and gravity. Venus is only a little bit smaller than our home planet, with a mass of about 80% of Earth’s.

Venus is not a gas planet, but a rocky planet. The interior of Venus is made of a metallic iron core that’s roughly 2,400 miles (6,000 km) wide. Venus’ molten rocky mantle is roughly 1,200 miles (3,000 km) thick. Venus’ crust is mostly basalt and is estimated to be 6 to 12 miles (10 to 20 km) thick, on average.

Why Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system is rather complicated. Although Venus is not the planet closest to the sun, its dense atmosphere traps heat in a runaway version of the greenhouse effect that we see firsthand on Earth with global warming. As a result, temperatures on Venus reach 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius), which is more than hot enough to melt lead. Spacecraft have survived only a few hours after landing on the planet before being destroyed.

With scorching temperatures, Venus also has a hellish atmosphere, that consists mainly of carbon dioxide with clouds of sulfuric acid and only trace amounts of water. The atmosphere of Venus is heavier than that of any other planet, leading to a surface pressure that’s over 90 times that of Earth — similar to the pressure that exists 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) deep in the ocean.

Venus’ surface is extremely dry. During the planet’s evolution, ultraviolet rays from the sun evaporated water quickly, keeping Venus in a prolonged molten state. There is no liquid water on its surface today because the scorching heat created by its ozone-filled atmosphere would cause water to immediately boil away.

Roughly two-thirds of the Venusian surface is covered by flat, smooth plains that are marred by thousands of volcanoes, some of which are still active today, ranging from about 0.5 to 150 miles (0.8 to 240 km) wide, with lava flows carving long, winding canals that are up to more than 3,000 miles (5,000 km) in length.

Six mountainous regions make up about one-third of the Venusian surface. One mountain range, called Maxwell, is about 540 miles (870 km) long and reaches up to some 7 miles (11.3 km) high, making it the highest feature on the planet.

Venus also possesses several surface features that are unlike anything on Earth. For example, Venus has coronae, or crowns — ring-like structures that range from roughly 95 to 1,300 miles (155 to 2100 km) wide. Scientists believe these formed when hot material beneath the planet’s crust rose, warping the planet’s surface. Venus also has tesserae, or tiles — raised areas in which many ridges and valleys have formed in different directions.

Venus has no known moons, which makes it nearly unique in our solar system. The only other designated planet without moons is Mercury, which is quite close to the sun. Scientists aren’t yet sure why some planets have moons and some do not, but what they can say is that each planet has a unique and complex history and that may in part contribute to how moons formed, or didn’t form.

What is Venus’ orbit like?

Venus takes 243 Earth days to rotate on its axis, which is by far the slowest of any of the major planets. In fact, its day is longer than its year, and that may be due to the thick atmosphere of Venus serving as a big brake on the planet’s rotation. And, because of this sluggish spin, its metal core cannot generate a magnetic field similar to Earth’s. The magnetic field of Venus is 0.000015 times that of Earth’s magnetic field.

Average distance from the sun: 67 million miles (108 million km).

Perihelion (closest approach to the sun): 66,785,000 miles (107,480,000 km).

Aphelion (farthest distance from the sun): 67,692,000 miles (108,941,000 km).

If viewed from above, Venus rotates on its axis in a direction that’s the opposite of most planets’. That means on Venus, the sun would appear to rise in the west and set in the east. On Earth, the sun appears to rise in the east and set in the west.

The Venusian year — the time it takes to orbit the sun — is about 225 Earth days long. Normally, that would mean that days on Venus would be longer than years. However, because of Venus’ curious retrograde rotation, the time from one sunrise to the next is only about 117 Earth days long. The last time we saw Venus transit in front of the sun was in 2012, and the next time will be in 2117.

Venus’ atmosphere

The very top layer of Venus’ clouds zips around the planet every four Earth days, propelled by hurricane-force winds traveling roughly 224 mph (360 kph). This superrotation of the planet’s atmosphere, some 60 times faster than Venus itself rotates, might be one of Venus’ biggest mysteries.

The clouds also carry signs of meteorological events known as gravity waves, caused when winds blow over geological features, causing rises and falls in the layers of air. The winds at the planet’s surface are much slower, estimated to be just a few miles per hour.

Unusual stripes in the upper clouds of Venus are dubbed “blue absorbers” or “ultraviolet absorbers” because they strongly absorb light in the blue and ultraviolet wavelengths. These are soaking up a huge amount of energy — nearly half of the total solar energy the planet absorbs. As such, they seem to play a major role in keeping Venus as hellish as it is. Their exact composition remains uncertain; Some scientists suggest it could even be life, although many things would need to be ruled out before that conclusion is accepted.

Related: The 10 Weirdest Facts About Venus

The Venus Express spacecraft, a European Space Agency mission that operated between 2005 and 2014, found evidence of lightning on the planet, which formed within clouds of sulfuric acid, unlike Earth’s lightning, which forms in clouds of water. Venus’ lightning is unique in the solar system. It is of particular interest to scientists because it’s possible that electrical discharges from lightning could help form the molecules needed to jumpstart life, which is what some scientists believe happened on Earth.

Exploring Venus

The United States, Soviet Union, European Space Agency and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency have deployed many spacecraft to Venus — more than 20 so far. NASA’s Mariner 2 came within 21,600 miles (34,760 km) of Venus in 1962, making it the first planet to be observed by a passing spacecraft. The Soviet Union’s Venera 7 was the first spacecraft to land on another planet, having landed on Venus in December 1970. Venera 9 returned the first photographs of the Venusian surface. The first Venusian orbiter, NASA’s Magellan, generated maps of 98% of the planet’s surface, showing features as small as 330 feet (100 meters) across.

The European Space Agency’s Venus Express spent eight years in orbit around Venus with a large variety of instruments and confirmed the presence of lightning there. In August 2014, as the satellite began wrapping up its mission, controllers engaged in a month-long maneuver that plunged the spacecraft into the outer layers of the planet’s atmosphere. Venus Express survived the daring journey, then moved into a higher orbit, where it spent several months. By December 2014, the spacecraft ran out of propellant and eventually burned up in Venus’ atmosphere.

Related: Venera timeline: The Soviet Union’s Venus missions in pictures

Japan’s Akatsuki mission launched to Venus in 2010, but the spacecraft’s main engine died during a pivotal orbit-insertion burn, sending the craft hurtling into space. Using smaller thrusters, the Japanese team successfully performed a burn to correct the spacecraft’s course. A subsequent burn in November 2015 put Akatsuki into orbit around the planet. In 2017, Akatsuki spotted another huge “gravity wave” in Venus’ atmosphere. The spacecraft still orbits Venus to this day, studying the planet’s weather patterns and searching for active volcanoes.

As of at least late 2019, NASA and the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Space Research Institute have discussed collaborating on the Venera-D mission, which would include an orbiter, a lander and perhaps a solar-powered airship.

“We’re at the pen-and-paper stage where we’re considering what science questions …we want this mission to answer and what components of a mission would best answer those questions,” Tracy Gregg, a planetary geologist at the University at Buffalo, told Space.com in 2018. “The earliest possible launch date we’d be looking at is 2026, and who knows if we could meet that.”

NASA has more recently funded several extremely early-stage mission concepts that could look at Venus in the coming decades, under the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts Program. This includes a “steampunk” rover that would use old-school levers instead of electronics (which would fry in Venus’ atmosphere) and a balloon that would check out Venus from low altitudes. Separately, some NASA researchers have been investigating the possibility of using airships to explore the more temperate regions of Venus’ atmosphere.

In 2021, NASA announced two new missions to Venus that will launch by 2030.

The agency announced on June 2, 2021, that they will be sending missions DAVINCI+ and VERITAS, chosen from a shortlist of four spacecraft, for the next round of Discovery missions to Venus.

DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry and Imaging) will dive through the planet’s atmosphere, studying how it changes over time. VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy) will map the planet’s surface from its orbit using radar.

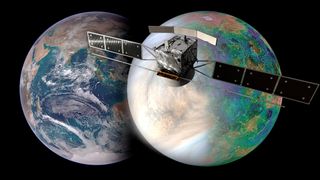

On June 12, 2021, ESA announced its next Venus orbiter – EnVision. “A new era in the exploration of our closest, yet wildly different, Solar System neighbour awaits us,” Günther Hasinger, ESA’s director of science, said in a statement. “Together with the newly announced NASA-led Venus missions, we will have an extremely comprehensive science program at this enigmatic planet well into the next decade.” ESA hopes to launch the mission to Venus in the early 2030s.

Private space explorers are also eyeing Venus. Rocket Lab announced in 2020 that it plans to ferry a spacecraft to Venus to deploy a probe within the atmosphere. The spacecraft, according to a 2022 paper, has a 2-pound (1 kg) instrument on board and is designed to survive five minutes in the clouds of Venus in a more temperate, Earth-like zone roughly 30 to 37 miles (48 to 60 kilometers) above the surface. It’s all part of a greater search for life on Venus, which got a kick-start that year from an intriguing new study.

Is there life on Venus?

While destinations in our solar system like the moons Enceladus or Titan or even planet Mars are currently the go-to spots to search for signs of extraterrestrial life.

But a breakthrough scientific discovery in 2020 suddenly had scientists discussing whether or not it was possible that life could somehow exist in the present-day hellish atmospheres of Venus.

Now, scientists think that it is most likely that, billions of years ago, Venus could have been habitable and fairly similar to current-day Earth. But since then, it has undergone a drastic greenhouse effect that has resulted in Venus’ current iteration with scorching surface temperatures and an atmosphere that many describe as “hellish.”

However, in 2020, scientists revealed the discovery of a strange chemical in the planet’s clouds that some think could be a sign of life: phosphine.

Phosphine is a chemical compound that has been seen on Earth as well as on Jupiter and Saturn. Scientists think that, on Venus, it could appear as it does on Earth, for very short amounts of time in the planet’s atmosphere.

But what does this phosphine discovery have to do with the search for life?

Well, while phosphine exists in strange ways such as rat poison, it has also been spotted alongside groups of certain microorganisms and some scientists think that, on Earth, the compound is produced by microbes as they decay chemically.

This has caused some to suspect that, if microbes could create phosphine, then perhaps microbes might be responsible for the phosphine in Venus’ atmosphere. Since the discovery, there have been follow-up analyses that have made some doubt whether or not the compound is created by microbes, but scientists are continuing to investigate, especially with new missions planned for the planet.

Further, scientists searched for evidence of microbe waste (or poop) in a 2022 study and found no evidence of any activity. There were no spectral “fingerprints” suggesting active life within the atmosphere, which makes the premise of life hard to prove absent more compelling evidence, the authors said.

Terraforming Venus

Science fiction is replete with scenarios where astronauts terraform a planet to make it more Earth-like. How this could happen and whether it is feasible are matters of tremendous uncertainty. Most often, scientists and science fiction fans talk about terraforming Mars because the Red Planet is a little more habitable to humans than Venus (what with the lack of massive active eruptions, as a start.)

Terraforming any planet is sure to bring up ethical questions about how to protect any life that might be there, along with how to preserve any information that life left behind. (Venus is not hospitable to life as we know it, but one can never be too sure.)

Assuming we do want to go ahead with terraforming Venus, working on this would require an ocean and some sort of weathering process, a proposal from 2020 suggests. With enough water (assuming we could access tremendous amounts of the stuff) it might be possible to remove dust from the air and to get the atmospheric carbon dioxide to condense onto the surface. One possible way of making this happen could be to throw immense numbers of icy objects, like comets, into the atmosphere of Venus; how to get that to happen is another question, of course.

A 1991 proposal from British scientist Paul Birch has an alternative method: to somehow send out trillions of tons of hydrogen from gas giant planets like Jupiter. (The hydrogen, he said, would turn atmospheric carbon dioxide into water, with a big side of granite.) Venus would also need to be cooled down from the scorching sun using some kind of sun shade, which has the side effect of collecting solar energy for potential human or robotic use.

Venus expert Q&A

We asked Jim Garvin (Principal Investigator on NASA’s DAVINCI mission to Venus), Stephanie Getty (DAVINCI Deputy Principal Investigator) and Giada Arney (DAVINCI Deputy Principal Investigator) a few frequently asked questions about the planet.

Why is Venus the hottest planet?

Venus’ current environment is the result of a “greenhouse effect” that has allowed its massive CO2 atmosphere to intake the heat of the sun and retain that heat over time like a greenhouse for flowers here on Earth.

Were it not for this greenhouse effect, even with Venus’ location closer to the sun by about 25% relative to our Earth (which means Venus receives twice as much energy from the sun as Earth), its surface and atmosphere may have been more Earth-like in the past, with climate models suggesting that it could have been more clement, i.e., 50–80 degrees C (122–176 F) rather than 440-460 degrees C (824–860 F).

How Venus developed this greenhouse effect so prominently is a key question about our sister planet. It is possible that sustained volcanism on a planet that lost its surface oceans of liquid water allowed for more heat energy from active eruptions to also heat the atmosphere from below, influencing the thick deck of clouds that serves today to keep the heat deep in Venus’s atmosphere. On Earth, carbon dioxide outgassed by volcanoes is recycled back into the planet’s interior on geological timescales through plate tectonics; on Venus, with no plate tectonics, carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere as a robust greenhouse gas.

What color is Venus?

From orbiting spacecraft such as the Venus Express (ESA) and Akatsuki (JAXA), the visible “color” of Venus’ atmosphere is very bland without the rich colors that one can see for example at Jupiter.

Venus’ atmosphere presents a globally encircling cloud deck tens of km in thickness, made of chemicals that reflect and absorb the illumination form the sun. Due to these sulfuric acid clouds, Venus is effectively white or possibly a very pale yellow to our eyes. These clouds are also very bright, reflecting approximately 70% of the solar energy that hits them back to space.

The chemistry of the upper atmosphere with its clouds controls what our eyes would see if we were seeing Venus, and the false-color views of the beautiful planet that are often shown reflect the ultraviolet (not visible to human eyes) variations that include a mystery absorber. There is much to learn about the UV, visible, near-infrared and beyond character of the upper atmosphere of Venus, and NASA’s DAVINCI mission will carry a new class of “hyperspectral” camera to measure it at very high spectral resolution for the first time from flybys.

Why is Venus sometimes referred to as Earth’s twin?

Venus and Earth are very similar in size, bulk density, location relative to our sun (parent star), and that makes us “planetary twins” in one sense. Such similarities are important because Venus did not evolve to be Earth-like for reasons that remain a key question in planetary science. It is possible that Venus was more like Earth in the past, with habitable surface temperatures and oceans of water perhaps up to 300m (984ft) deep (Earth’s mean ocean depths are 2700m/8850ft), but over time, the histories of these planets were driven apart.

There are key differences between modern Earth and Venus. First, Venus receives about twice the energy from the sun as Earth so it will naturally be hotter. Its present atmosphere is dominantly CO2 and 90 times thicker than Earth’s atmosphere, rather than Earth’s unique N2-O2 atmosphere modified by our planet’s biosphere, which is an important difference that reflects its possible history post-formation.

Venus has a very thick and globally-encircling, cloud deck with the mid-level clouds being made of sulfuric acid droplets (aerosols) and other not yet well-measured gases. Venus is also a slow rotator relative to Earth and in effect, its solar day is longer than the time it takes (one Venus year) to go around the sun, and it even rotates backward relative to the other planets. This makes it a very unique planet to compare to our Earth with its 24-hour day and 365.25-day year.

Thus, Venus may be an ideal example of a terrestrial-sized planet that lost its “habitability” over time for various reasons which three upcoming missions will address, each in different ways, in the early to mid-2030s.

DAVINCI will plunge through Venus’ atmosphere. What is it designed to look for?

NASA’s DAVINCI mission is designed to answer long-standing questions about how Venus’s atmosphere evolved and whether there remain chemical signatures of past oceans or even indicators of the role of water in shaping some of the highland regions on Venus, which make up about 8% of the planet’s surface area.

DAVINCI will conduct special flyby remote-sensing observations designed to measure the chemistry and motions of the upper cloud deck, as well as mapping the regional-scale compositional differences between highlands known as tesserae (such as Alpha and Ovda Regio) and the dominant rolling plains that are believed to be basaltic like the lavas that erupt in Hawaii and Iceland.

DAVINCI also includes a 3.5-foot-diameter deep atmosphere probe, which is a flying chemistry/imaging/environment laboratory that will “take the plunge” into the Venusian atmosphere, and during its hour-long descent from the top of the clouds to the surface in a mountainous region bigger than Texas (Alpha Regio), it will make definitive measurements of noble gases, trace gases, the ratio of heavy to light hydrogen in water vapor and the role of sulfur in trace gases all the way to the foreboding near-surface, while measuring the environmental conditions every 15–50 m. These measurements will help us understand the current state of Venus, its possible past water, and how the planet formed and evolved.

DAVINCI will also conduct the first-ever descent imaging experiment using a near-infrared camera designed to distinguish rock types from beneath the clouds at scales as fine as ~10m while also measuring topography and landscape geomorphology. Many of DAVINCI’s measurements have never been made in any planetary atmosphere before and these new data will inform scientists who build predictive models of how planets with big atmospheres change over time in response to volcanism, large-body impacts, and other effects (e.g., the loss of oceans).

DAVINCI is intended to fill in gaps that the science community has documented since the mid-1980s while paving the way for understanding how to compare exoplanets that appear to be Venus-like to the “real” Venus. Its measurements and outcomes will inform the history of Venus as a planet with a large atmosphere for decades, and permit other orbiter missions to conduct critical next-generation mapping of the planet’s crust and shallow interior.

In the context of our overall understanding of Venus and its history, how important is it that we understand its atmosphere better?

Venus is noteworthy because of its large atmosphere atop a planetary surface obscured by a thick deck of clouds. As of today (2023), we have very limited knowledge of the chemistry and environments of this atmosphere, especially below the clouds, nor do we understand the critical noble (inert) gases which are “chemical fingerprints” of the history of planetary processes, like “fossils”.

We need to understand Venus to know how our own planet’s destiny may unfold over long periods of time and to understand the history of Venus alongside Earth and Mars. While the large, hot, and enigmatic Venusian atmosphere may seem bizarre and even irrelevant, it is Mother Nature’s laboratory for us to explore with 21st-century tools (as we have on DAVINCI’s deep atmosphere probe) to learn about the details of how another planetary atmosphere–climate–ocean system may have worked.

We only know our own, and Mars’ is too rarified to have been as significant as that of Venus. Thus, Venus is key to understanding how different evolutionary pathways operate for planets of similar sizes and roughly the same distance from the sun. This is an important aspect of what we need to know about Venus as we search for Venus-like exoplanets over the coming decades thanks to observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope.